The Jewish Slave Trade

“The principal purchasers of slaves were found among the Jews… [T]hey seemed to be always and everywhere at hand to buy, and to have the means equally ready to pay.” – Lady Magnus, Outlines of Jewish History

This article sets to outline the Jewish involvement in the slave trade and slave ownership, particularly in the United States of America.

The Spanish Jews accumulated substantial wealth through their dealings in Christian slaves and attained significant prominence within Spain’s social and political order. [1]

“The golden age of Jewry in Spain owed some of its wealth to an international network of Jewish slave traders. Bohemian Jews purchased Slavonians and sold to Spanish Jews for resale to the Moors.” [1]

The rapid growth of the slave trade, involving both Africans and Indians, saw the involvement of some Jews acting as agents for the royal families of Spain and Portugal. [2]

As the slave trade became a significant aspect of Jewish economic life, Jews brought in Africans in substantial numbers and stored them in warehouses. [21]

According to Jewish author Herbert I. Bloom, “[the] slave trade was one of the most important Jewish activities here as elsewhere in the colonies.” [23]

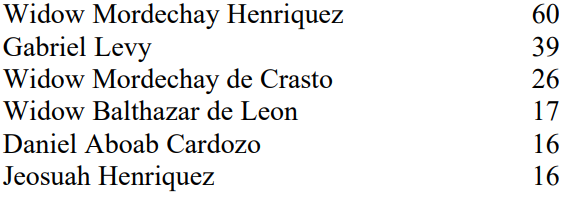

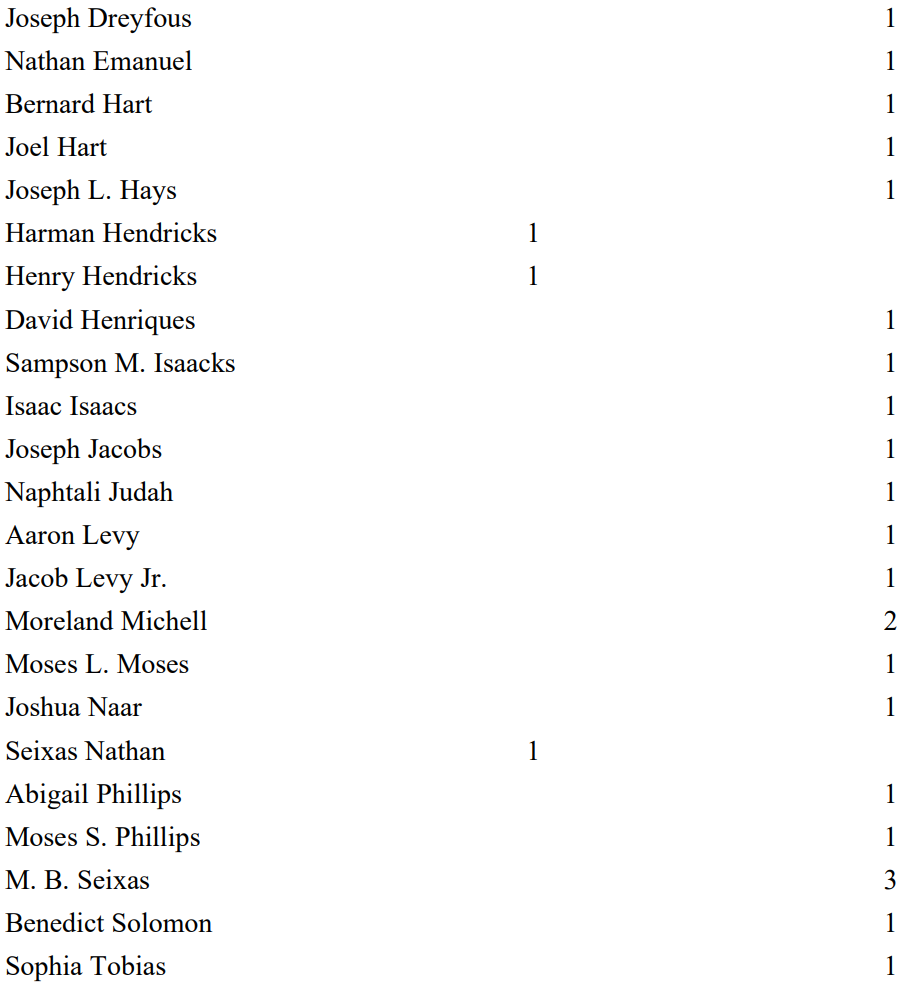

The following is a list of Jewish buyers of Black slaves from the Dutch West India Company in Surinam, February 21, 22,23,1707. [24]

During the period of 1686 to 1710, Jewish involvement in the slave trade with the Dutch West India Company was substantial. Records indicate that Jews were recorded as the owners of approximately 867 African slaves in this 25-year timeframe. [30]

[56]

[56] [57]

[57]

[63]

[63]

[66]

[66]

[67]

[67]

[68]

[68]

[71]

[71] [72]

[72]

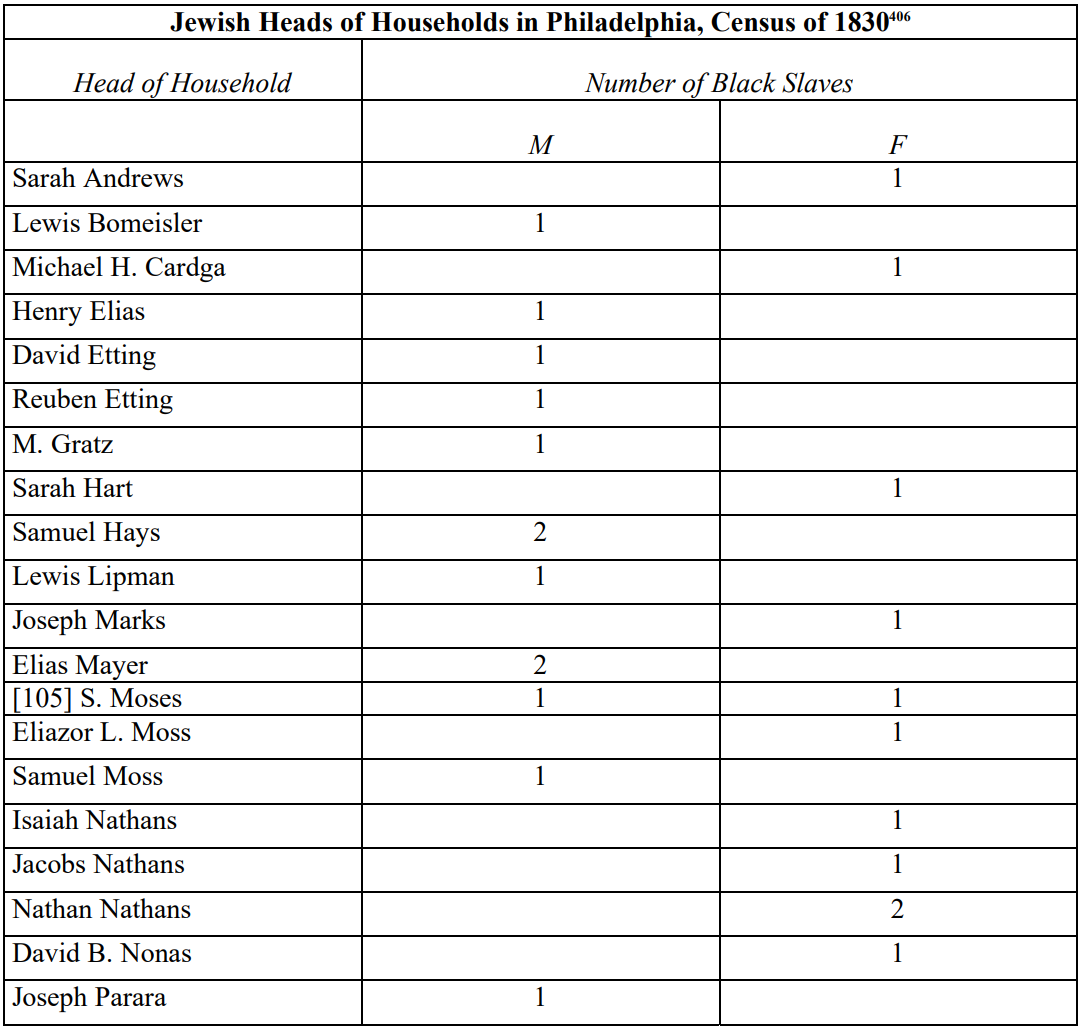

[101] [102]

[101] [102]

Source: [1] Harry L. Golden and Martin Rywell, Jews in American History: Their Contribution to the United States of America (Charlotte: Henry Lewis Martin Co., 1950), p. 5; Feuerlicht, p. 39. Also, Jewish Encyclopedia, vol. 11, p. 402

Source: [2] 43 Burkholder and Johnson, p. 28; Liebman, The Jews in New Spain, p. 47

Source: [3] 6 Rufus Learsi, The Jews in America: A History (New York: KTAV Publishing House, Inc., 1972), p. 25

Source: [4] Galloway, p. 81: “As sugar grew in significance, so did African slavery: from about 6,000 slaves in 1643 to 20,000 in 1655 and 38,782 in 1680.” See Learsi, p. 22. He characterizes the settlements as being based on a “slave economy on which all the plantations of the New World rested.”

Source: [5] Marc Lee Raphael, Jews and Judaism in the United States: A Documentary History (New York: Behrman House, Inc., 1983), p. 14

Source: [6] For examples see Herbert S. Klein, African Slavery in Latin America and the Caribbean (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), pp. 133,134

Source: [7] Arkin, AJEH, p. 199. Professor Gilberto Freyre describes the Brazilian plantation owners of this period in his book, The Masters and the Slaves – A Study in the Development of Brazilian Civilisation, as follows: Power came to be concentrated in the hands of the country squires. They were the lords of the earth and the lords of the men and women also. Their houses were the expression of the enormous feudal might – ugly, strong, thick walls, deep foundations. For safety’s sake, as a precaution against pirates and against the natives and the Africans, the proprietors built these fortresses and buried gold and their jewels beneath the floors. Slothful, but filled to overflowing with sexual concerns, the life of the sugar planters tended to become a life that was lived in a hammock. A stationary hammock with the master taking his ease, sleeping, dozing. Or a hammock on the move with the master on a journey or a promenade beneath the heavy draperies or curtains. He did not move from the hammock to give orders to his Negroes, to have letters written by his plantation clerk or chaplain, or to play a game of backgammon with some relative or friend. It was in a hammock that, after breakfast or dinner, they let their food settle as they lay picking their teeth, smoking a cigar, belching loudly, emitting wind and allowing themselves to be fanned or searched for lice by the piccaninnies as they scratched their feet or genitals – some of them out of vicious habits, others because of venereal or skin disease. For a summary of the conditions of slavery in this period, particularly the treatment of African and Indian women, see Sean O’Callaghan’s, Damaged Baggage: The White Slave Trade and Narcotics Traffic in the Americas (London: Robert Hale, 1969), pp. 15-32.; Galloway, p. 72: “As on Hispaniola, the average plantation in Brazil had about 100 slaves …. Even as late as 1583, two-thirds of the slaves on the engenhos of Pernambuco were Indian.” There are also other corroborating statements of Jewish wealth including those in George Alexander Kohut’s article, “Jewish Martyrs of the Inquisition in South America,” PAJHS, vol. 4 (1896), pp. 104-5: “The Marranos appear to have been quite prosperous for a while…”; and on pages 127-28 Mr. Kohut quotes from R. G. Watson’s, Spanish and Portuguese South America During the Colonial Period (London: 1884) vol. 2, p. 119: “If the New Christians were in Brazil a despised race, they could at any rate count on opportunities of gaining wealth and retaining it when gained.”

Source: [8] Arkin, AJEH, p. 200; Arnold Wiznitzer confirms in Jews in Colonial Brazil (Morningside Heights, New York: Columbia University Press, 1960), pp. 50-1, that, In return for a payment of 200,000 cruzados the New Christian merchants, by a royal decree of July 31, 1601, had been granted the right to trade with the colonies, but in 1610 this concession had been revoked. The Portuguese New Christian merchants suffered tremendous losses as a result of this act of revocation, since almost all of the country’s export trade had been in their hands. Friedman, “Sugar,” p. 307, says that in Brazil, “Many [Jews] became successful planters and mill owners, and not a few became sugar brokers and slave dealers or combined both operations, bartering slaves against sugar.” Mr. Friedman referenced N. Deerr, The History of Sugar, 2 vols. (London: Chapman & Hall, Ltd., 1949), vol. 1, p. 107; Galloway, p. 79, describes the Jewish involvement: “In both Pernambuco and Amsterdam, the Sephardic Jews became involved in the sugar trade as financiers and merchants; in Pernambuco a few became [plantation masters].” Dimont, p. 30, says that sugar production was “an industry controlled by the Marranos.”

Source: [9] Stephen Alexander Fortune, Merchants and Jews: The Struggle for the British West Indian Caribbean, 1650-1750 (Gainesville: University Presses of Florida, 1984), p. 71

Source: [10] Golden and Rywell, pp. 11, 13; EAJA, pp. 125-26 and notes 27 and 28. Bloom states that there is no accounting of the exact investment of the Jews in the Company but cites the works of others who concur that while their numbers were not more than 10%, their investment was much greater. Eighteen Jews of Amsterdam, by 1623, had reportedly invested 36,100 guilders of the 7,108,106 guilders raised (one half of 1 %), in the West India Company though actual figures have not been determined. Later, the influence of these investors in the establishment of a Jewish community in colonia New York, over the objection of the Company’s own governor, suggests that the reported investment of the Jews is understated. See this document, section entitled, “New York.” See also Arkin, AJEH, p. 201 and Jonathan I. Israel, The Dutch Republic and the Hispanic World 1606-1661 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1982), p. 127. It is reputed that Dutch Jews may have owned as much as “five-eighths” of the Dutch East India Company, whose profits from precious metals, spices, coral and drugs were magnificent. See John M. Shaftesley, Remember the Days: Essays on Anglo-Jewish History presented to Cecil Roth by members of the Council of The Jewish Historical Society of England (The Jewish Historical Society of England, 1966), pp. 127,135,139. Another venture confirms Jewish interest in such enterprise. In describing the formation of the armored shipping Brazil Company, David Grant Smith, pp. 237-38, suggests that “New Christians” were considered to be “the only possible source for funds of such magnitude.”

Source: [11] Swetschinski, p. 236; Wiznitzer, Jews in Colonial Brazil, pp. 67-8; Smith, pp. 246-47; Israel, The Dutch Republic, p. 276

Source: [12] Herbert I. Bloom, The Economic Activities of the Jews of Amsterdam in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (Port Washington, New York/London: Kennikat Press, 1937) p. 133

Source: [13] Bloom, “Book Reviews: The Dutch in Brazil, pp. 113, note 114

Source: [14] Wiznitzer, Jews in Colonial Brazil, pp. 72-3; Raphael, p. 14

Source: [15] Judith Laikin Elkin, Jews of the Latin American Republics (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1980) p. 17

Source: [16] 94 Emmanuel HJNA, p. 75 note no. 52. see also Liebman, New World Jewry, p. 170, Johan Hartog, Curaqao From Colonial Dependence to Autonomy (Aruba, Netherland Antilles, 1968), p. 178 and Swetschinski, p. 222

Source: [17] Emmanuel HJNA, p. 75; ibid, vol. 2, p. 747

Source: [18] Emmanuel HJNA, pp. 75-6 and note no. 55

Source: [19] Frederick P. Bowser, African Slave in Colonial Peru: 1524-1650 (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1974), p. 34; Wiernik, p. 34, reports that the “public facade” mentioned in this quote included Marranos or secret Jews taking some extraordinary actions: “…it was reported that the physicians of Bahia, who were mainly new-Christians, prescribed pork to their patients in order to lessen the suspicion that they were still adhering to Judaism.” See also Bertram Wallace Korn, The Early Jews of New Orleans (Waltham, Massachusetts: American Jewish Historical Society, 1969), pp. 3-4

Source: [20] Seymour B. Liebman, New World Jewry, p. 188

Source: [21] Marc Lee Raphael, Jews and Judaism in the United States: A Documentary History (New York: Behrman House, Inc., 1983), p. 24

Source: [22] Wiemik, p. 47; Encyclopaedia Judaica (Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House, Ltd., 1971), vol. 15, p. 530

Source: [23] Herbert I. Bloom, The Economic Activities of the Jews of Amsterdam in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (Port Washington, New York/London: Kennikat Press, 1937)

Source: [24] The Economic Activities of the Jews of Amsterdam, pp. 159-60. Other sales took place in March, 1707 where ten Jews bought slaves amounting to 10,400 guilders which was more than one-fourth of the total amount of money expended at the sale (38,605 guilders)

Source: [25] The Economic Activities of the Jews of Amsterdam, pp. 162-63; MCAJ1, 159; R. BijIsma, “David de Is. C. Nassy, Author of the Essai Historique sur Surinam,” in Robert Cohen, The Jewish Nation in Surinam, p. 6

Source: [26] Isaac S., and Susan A. Emmanuel, History of the Jews of the Netherland Antilles (Cincinnati: American Jewish Archives, 1973), p. 83, ibid, vol. 2, p. 681: “According to a letter of the Curaqoan Jews to the Amsterdam Parnassim, February 17, 1721, the shipping business was mainly a Jewish enterprise.” Liebman, New World Jewry, p. 183: “The ships were not only owned by Jews, but were manned by Jewish crews and sailed under the command of Jewish captains.”

Source: [27] Jacob Rader Marcus, The Colonial American Jew: 1492-1776 (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1970, 3 volumes), p. 120; Davis, p. 141

Source: [28] Isaac S., and Susan A. Emmanuel, History of the Jews of the Netherland Antilles (Cincinnati: American Jewish Archives, 1973), p. 75

Source: [29] EIkin, p. 18; Another well documented description of the Jewish settlement in Curaçao can be found in Jacob Rader Marcus, The Colonial American Jew: 1492-1776 (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1970, 3 volumes), pp. 180-87 passim

Source: [30] Isaac S., and Susan A. Emmanuel, History of the Jews of the Netherland Antilles (Cincinnati: American Jewish Archives, 1973), p. 78; It should again be noted as in Barbados, that Jews had every reason to underreport their taxable holdings – they were, after all, prominent as tax-collectors (tax-farmers). This, coupled with a lively smuggling trade with Africans as the prime profit making commodity, would cause one to question the validity of the slave holdings reported by the Jews. These figures, therefore, represent the lowest possible number of Africans held as slaves by the “chosen people.” See Samuel, p. 7

Source: [31] Isaac S., and Susan A. Emmanuel, History of the Jews of the Netherland Antilles (Cincinnati: American Jewish Archives, 1973), p. 228

Source: [32] Isaac S., and Susan A. Emmanuel, History of the Jews of the Netherland Antilles (Cincinnati: American Jewish Archives, 1973), p. 229

Source: [33] Isaac S., and Susan A. Emmanuel, History of the Jews of the Netherland Antilles (Cincinnati: American Jewish Archives, 1973), p. 228 note

Source: [34] Isaac S., and Susan A. Emmanuel, History of the Jews of the Netherland Antilles (Cincinnati: American Jewish Archives, 1973), p. 228

Source: [35] Isaac S., and Susan A. Emmanuel, History of the Jews of the Netherland Antilles (Cincinnati: American Jewish Archives, 1973), p. 228

Source: [36] Harold Sharfman, Jews on the Frontier (Chicago: Henry Regnery Company, 1977), p. 154

Source: [37] A more detailed documentation of their involvement is provided in the chapter entitled “Jews of the Black Holocaust.” Also, Hershkowitz, “New York,” pp. 29, 32, APPENDIX II

Source: [38] Rosenwaike, Edge of Greatness, pp. 119-23, Table A-6

Source: [39] Wolf and Whiteman, pp. 190-91

Source: [40] Feingold, Zion, p. 42; Raphael, p. 14; Rudolf Glanz, “Notes on Early Jewish Peddling in America,” Jewish Social Studies, vol. 7 (1945), p. 121: “Doubtless they were active in Indian trade, supplying the Army, and in real estate deals, but the center of their activities was triangular trade between the American colonies and the motherland via the West Indies.”

Source: [41] Jacob Rader Marcus, The Colonial American Jew: 1492-1776 (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1970, 3 volumes), p. 1528; According to Ira Rosenwaike, “An Estimate and Analysis of the Jewish Population of the United States in 1790,” Karp, JEA1, p. 393. Dimont, p. 44: “At the time of the Revolution, the Jewish community in Newport comprised but fifty to seventy-five Jewish families, but their wealth and prestige outstripped that of the Jewish community in New York.”

Source: [42] Rosenwaike, Edge of Greatness, p. 124, Table A-7

Source: [43] G. Cohen, pp. 84-5; See also Eugene 1. Bender, “Reflections on Negro-Jewish Relationships: The Historical Dimension,” Phylon, vol. 30 (1969), p. 60; Lewis M. Killian, White Southerners (Amherst: UMass Press, 1985), p. 73; Harry Simonhoff, Jewish Participants in the Civil War (New York: Arco Publishing Co., Inc., 1963), pp. 31011; Korn, “Jews and Negro Slavery,” p. 218

Source: [44] Leonard Dinnerstein, Uneasy At Home (New York: Columbia University Press, 1987), p. 86

Source: [45] Leonard Dinnerstein, Uneasy at Home, pp. 86-7; See also Wiernik, pp. 206-7

Source: [46] Julius Lester, lecture at Boston University, January 28, 1990; Weisbord and Stein, p. 20

Source: [47] Lenni Brenner, Jews in America Today (Secaucus, New Jersey: Lyle Stuart Inc., 1986) pp. 221-22

Source: [48] Salo W. Baron, Arcadius Kahan, Nachum Gross, ed., Economic History of the Jews (New York: Schocken Books, 1975), p. 274

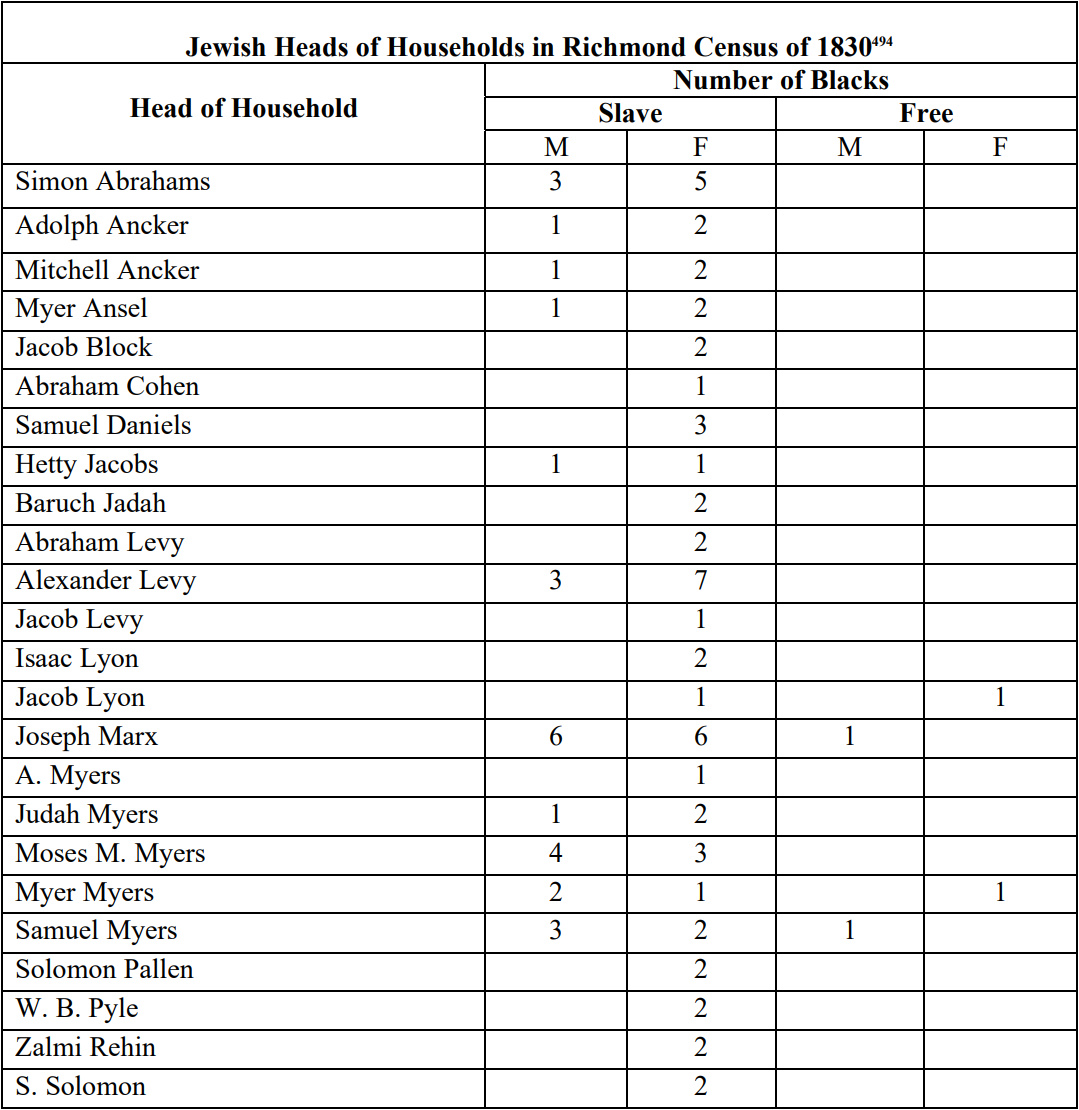

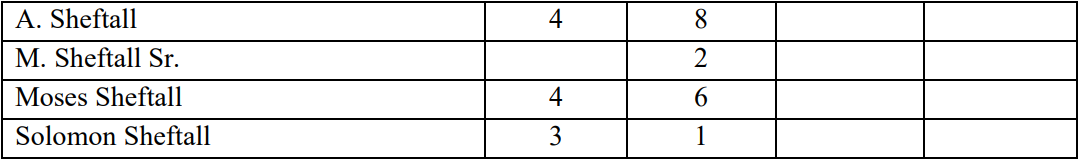

Source: [49] Salo W. Baron, Arcadius Kahan, Nachum Gross, ed., Economic History of the Jews (New York: Schocken Books, 1975), p. 274; Korn, “Jews and Negro Slavery,” pp. 181-82; Myron Bermon, Richmond’s Jewry 1769-1976: Shabbat in Shockoe (Charlottesville, Virginia: Jewish Community Federation of Richmond by University Press of Virginia, 1979), p. 166; Feldstein, p. 81

Source: [50] Harold Sharfman, Jews on the Frontier (Chicago: Henry Regnery Company, 1977), p. 152

Source: [51] Feingold, Zion, p. 62

Source: [52] Jacob Rader Marcus, Memoirs of American Jews 1775-1865 (New York: KTAV Publishing House, Inc., 1974, 3 volumes), p. 20

Source: [53] G. Cohen, p. 87

Source: [54] Rosenwaike, Edge of Greatness, p. 66

Source: [55] Ira Rosenwaike, “The Jewish Population of the United States as Estimated from the Census of 1820,” Abraham J. Karp, ed., The Jewish Experience in America: Selected Studies from the Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society (Waltham, Massachusetts, 1969, 3 volumes), p. 17

Source: [56] Rosenwaike, Edge of Greatness, p. 68, Table 21

Source: [57] Rosenwaike, Edge of Greatness, p. 67, Table A-20

Source: [58] “Some Old Papers Relating to the Newport Slave Trade,” Newport Historical Society Bulletin, no. 62 (July, 1927), p. 11, “And it is certain that Protestants, Quakers, and Jews were all holders of slaves. It was a question not of creed or race, but of the of sufficient money.”

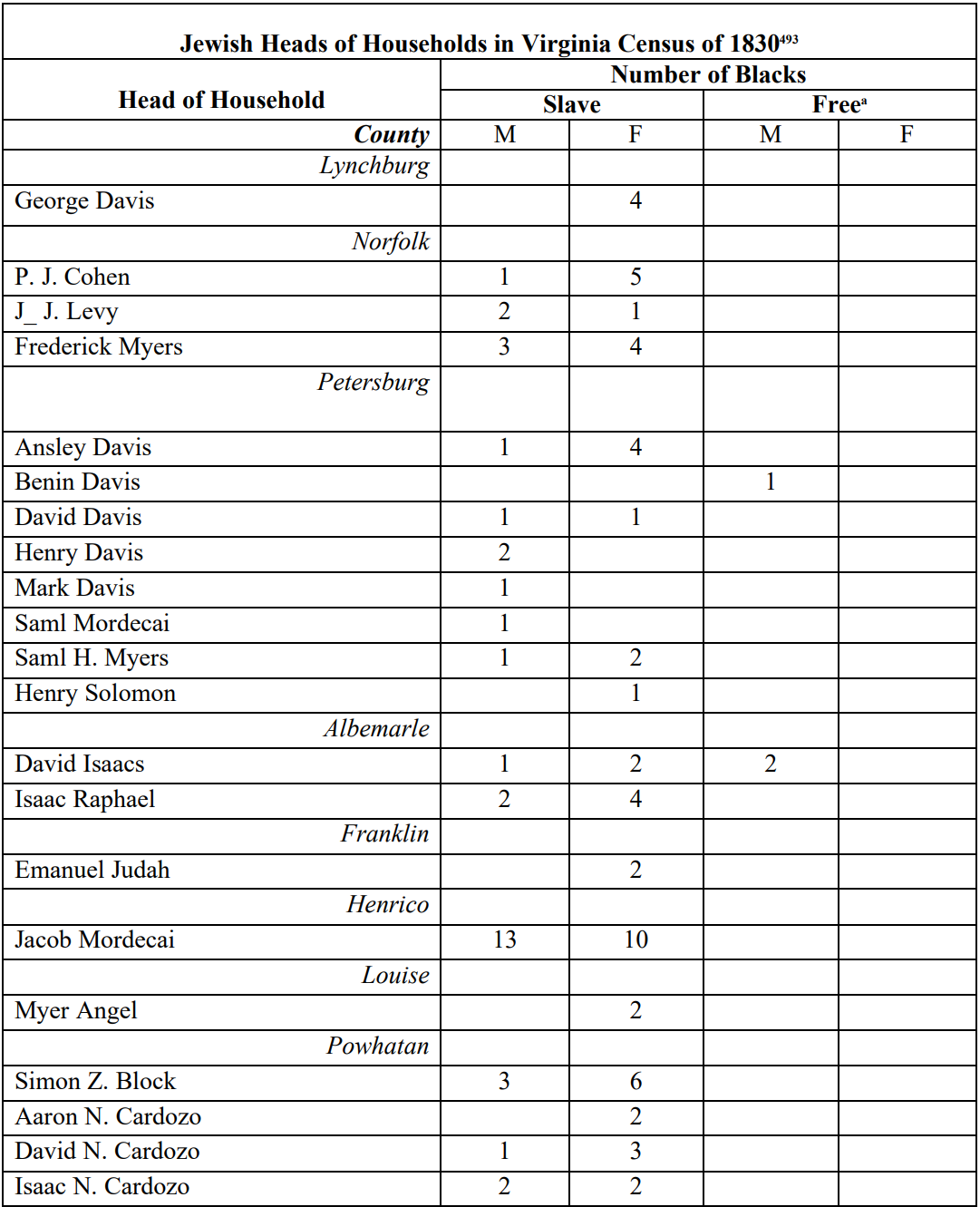

Source: [59] Hühner, “The Jews of Virginia,” p. 88; Golden and Rywell, p. 23

Source: [60] Jacob Rader Marcus, United States Jewry, 1776-1985 (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1989), p. 211, p. 28

Source: [61] Berman, p. 166; Feingold, Zion, p. 60: “[T]he possession of one or two house servants was fairly widespread. As many as a quarter of the South’s Jews may have fallen into this category… It is a clue to the relative prosperity of [Mississippi] Jewry because slave ownership was also an indication of wealth and social status.” This accounting, however, is of domestic servants only and makes no accounting of the Blacks held as stock in trade.

Source: [62] Rosenwaike, Edge of Greatness, pp. 132-33, Table A-1 1. (Excludes Richmond)

Source: [63] Rosenwaike, Edge of Greatness, p. 128, Table A-8

Source: [64] Jacob Rader Marcus, Early American Jewry (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1951, 2 volumes) p. 322

Source: [65] Jacob Rader Marcus, The Colonial American Jew: 1492-1776 (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1970, 3 volumes), p. 1504

Source: [66] Rosenwaike, Edge of Greatness, pp. 130-31, Table A-10

Source: [67] Rosenwaike, Edge of Greatness, p. 113-15, Table A-2

Source: [68] Rosenwaike, Edge of Greatness, p. 117, Table A-4

Source: [69] St. John, p. 60; Hühner, “The Jews of Georgia,” p. 82: “The reasons which ultimately induced most of the Jews to leave the colony had nothing whatever to do with religious prejudice.”

Source: [70] Jacob Rader Marcus, Memoirs of American Jews 1775-1865 (New York: KTAV Publishing House, Inc., 1974, 3 volumes), 2, p. 288

Source: [71] 7 Rosenwaike, Edge of Greatness, p. 129, Table A-9

Source: [72] Rosenwailke, Edge of Greatness, p. 118, Table A-5

Source: [73] Rabbi Leo E. Turitz and Evelyn Turitz, Jews in Early Mississippi (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1983), p. xvii; Learsi, p. 95, concurs. He states that the Jews of the South “embraced its cause promptly and enthusiastically.”

Source: [74] Roberta Strauss Feuerlicht, The Fate of the Jews: A People Torn Between Israeli Power and Jewish Ethics (New York: Times Books, 1983), p. 73

Source: [75] Salo W. Baron, Arcadius Kahan, Nachum Gross, ed., Economic History of the Jews (New York: Schocken Books, 1975), p. 274; Also Fishman, p. 8

Source: [76] Louis Ruchames, “Abolitionists and the Jews,” PAJHS, vol. 42 (1952), pp. 153-54; The complete text is in Schappes, pp. 332-33. The original source is The Thirteenth Annual Report of the American and Foreign AntiSlavery Society, pp. 114-15; See also Sokolow, p. 27.

Source: [77] Roberta Strauss Feuerlicht, The Fate of the Jews: A People Torn Between Israeli Power and Jewish Ethics (New York: Times Books, 1983), p. 187

Source: [78] Roberta Strauss Feuerlicht, The Fate of the Jews: A People Torn Between Israeli Power and Jewish Ethics (New York: Times Books, 1983), p. 39

Source: [79] Abraham J. Karp, Haven and Home: A History of Jews in America (New York: Schocken Books, 1985), p. 80; Karp, JEA3, p. 209

Source: [80] Encyclopaedia Judaica (Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House, Ltd., 1971), vol. 12, p. 932. Frequently discussed, however, was Jewish slavery, which was the centerpiece of their moral crusade. According to Robert V. Friedenberg, “Hear O Israel,” The History of American Jewish Preaching, 1654-1970 (Tuscaloosa and London: University of Alabama Press, 1989), p. 41: “By the 1850s, there were at least sixty Jewish religious leaders in the country, of whom at least eighteen have left us printed sermons.” Friedenberg, p. 46: “It is highly significant that the first important statement on slavery to be made from any Jewish pulpit in the United States was not made until January 1861, after South Carolina had already left the Union over the question of slavery and while six other states were in the process of deciding to do the same.” See also Korn, Civil War, pp. 29-30

Source: [81] Arthur Hertzberg, The Jews in America: Four Centuries of an Uneasy Encounter: A History (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1989), pp. 123-24

Source: [82] Korn, Civil War, p. 29 and on pp. 88-90, Michelbacher also composed a prayer for his cause which read in part: Be unto the Army of this Confederacy, as thou were of old, unto us, thy chosen people – Inspire them with patriotism! Give them when marching to meet, or, overtake the enemy, the wings of the eagle – in the camp be Thou their watch and ward – and in the battle strike for them O Almighty God of Israel, as thou didst strike for thy people on the plains of Canaan – guide them O Lord of Battles, into the paths of victory, guard them from the shaft and missile of the enemy…” See also Lewis M. Killian, White Southerners (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1985), p. 73; Korn, Civil War, p. 29; Feldstein, pp. 100-1: Rabbi Michaelbacher justified the enslavement and the prison-like atmosphere of the slave states in this prayer, reasoning that it was the only means to prevent a repetition of the Saint Dominique massacre of the 1790s: The man servants and maid servants Thou has given unto us, that we may be merciful to them in righteousness and bear rule over them, the enemy are attempting to seduce, that they, too, may turn against us, whom Thou has appointed over them as instructors in Thy wise dispensation. Behold, O God, [the abolitionists] invite our manservants to insurrection, and they place weapons of death and the fire of desolation in their hands that we may become an easy prey unto them; they beguile them from the path of duty that they may waylay their masters, to assassinate and to slay the men, women and children of the people that trust only in Thee. In this wicked thought, let them be frustrated, and cause them to fall into the pit of destruction, which in the abomination of their evil intents they digged out for us, our brothers and sisters, our wives and our children.

Source: [83] Stanley Feldstein, The Land That I Show You (New York: Anchor Press/ Doubleday, 1978), p. 97

Source: [84] Korn, Civil War, pp. 29-30; Karp, Hawn and Home, p. 80

Source: [85] Kaganoff and Urofsky, p. 29; Feldstein, p. 96

Source: [86] Jacob Rader Marcus, Studies in American Jewish History (Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press, 1969), p. 38

Source: [87] Korn, “Jews and Negro Slavery,” p. 215. Certainly, no Jews who came to live in the antebellum South were deeply affected by abolitionism, and though their ethical anxiety over the peculiar institution was “sometimes demonstrated,” wrote Stephen J. Whitfield, “but not abundantly.” See Whitfield, Voices of Jacob, Hands of Esau: Jews in American Life and Thought (New York: Archon Books, 1984), p. 226

Source: [88] Oscar R. Williams, Jr., “Historical Impressions of Black-Jewish Relations Prior to World War II,” Negro History Bulletin, vol. 40 (1977), p. 728

Source: [89] Sokolow, p. 27. In Barbados, for instance, the Jews regarded manumission as “a curious eccentricity.” See Samuel, pp. 46-7

Source: [90] Hugh H. Smythe, Martin S. Price, “The American Jew and Negro Slavery,” The Midwest journal, vol. 7, no. 4 (1955-56), p. 318; Korn, Civil War, p. 27, Feuerlicht, p. 76

Source: [91] Fein, “Baltimore Jews,” p. 324. The term 48’ers refers to the immigrants who arrived en masse in 1848, primarily from Germany and many of whom were Jewish.

Source: [92] Karp, Haven and Home, p. 80

Source: [93] Korn, Civil War, p. 253, note 76

Source: [94] Korn, Civil War, p. 253, note 76

Source: [95] Jonathan D. Sarna, Jacksonian few: The Two Worlds of Mordecai Noah (New York: Holmes and Meir Publishers, 1981), pp. 111 and 197 note 52; Bernard Postal & Lionel Koppman, Guess Who’s Jewish in American History (New York: Shopolsky Books, 1986), p. 19; EJ, vol. 12, p. 1198; Joseph R. Rosenbloom, A Biographical Dictionary of Early American Jews: Colonial Times through 1800 (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press 1960), p. 134

Source: [96] Jonathan D. Sarna, Jacksonian few: The Two Worlds of Mordecai Noah (New York: Holmes and Meir Publishers, 1981), p. 110

Source: [97] Korn, “Jews and Negro Slavery,” p. 182

Source: [98] Korn, “Jews and Negro Slavery,” p. 182

Source: [99] Rosenwaike, Edge of Greatness, pp. 134-38, Table A-12

Source: [100] Malcolm H. Stern, “Some Additions and Corrections to Rosenwaike’s ‘An Estimate and Analysis of the Jewish Population of the United States in 1790,”‘ AIHQ, vol. 53 (1964), pp. 285-89: Ira Rosenwaike’s original article is in PAIHS, vol. 50, no. 1 (March, 1961), pp. 23-67

Source: [101] Rosenwaike, “Jewish Population of 1820,” pp, 19A-13

Source: [102] Rosenwaike, Edge of Greatness, p. 70, Table 22

Source: [103] Liebman, New World Jewry, p. 183

Source: [104] Jacob Rader Marcus, American Jewry: Documents of the Eighteenth Century (Cincinnati: Hebrew College Union Press, 1959), pp. 392, 416, 448; Schappes, pp. 58, 334, 569, 583, 627; Jay Coughtry, The Notorious Triangle: Rhode Island and the African Slave Trade, 1700-1807 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1981); Donnan, passim; Virginia Bever Platt, “And Don’t Forget the Guinea Voyage”: The Slave Trade of Aaron Lopez of Newport,” William and Mary Quarterly, vol. 32, no. 4 (1975), p. 603; Emmanuel, vol. 2, passim; Kohler, “Newport,” p. 73; Jonathan D. Sarna, Benny Kraut, Samuel K. Joseph, Jews and the Founding of the Republic (New York: Markus Wiener Publishing), p. 45

Source: [105] Freund, pp. 35, 75-6, Samuel Oppenheim, “Jewish Owners of Ships Registered at the Port of Philadelphia, 1730-1775,” PAJHS, vol. 26 (1918), pp. 235-36, Broches, pp. 12,14. Kohler, “New York,” p. 83; Libo and Howe, p. 46; Lee M. Friedman, Jewish Pioneers and Patriots, p. 90; Korn, Jews of New Orleans, p. 93; Irwin S. Rhodes, References to Jews in the Newport Mercury, 1758-1786 (Cincinnati: American Jewish Archives, 1961), pp. 3,13,15; Kohler, “Newport,” p. 73, lists Myer Pollack as owner of a ship Nancy. Hershkowitz, “Wills of Early New York Jews, 1743 – 1774,” AJHQ, vol, 56 (1966-67), p. 168. Leo Hershkowitz, “New York,” p. 27; Feingold, Zion, p. 45; MEA11, 204. See also Emmanuel, vol. 2, Appendix 3, pp. 681-738, for lists of Jewish owned ships

Source: [106] Wilfred S. Samuel, A Review of The jewish Colonists in Barbados in the Year 1680 (London: Purnell & Sons, Ltd.,1936), pp. 13,92

Source: [107] Korn, “Jews and Negro Slavery,” p. 193

Source: [108] David De Sola Pool, Portraits Etched in Stone: Early Jewish Settlers, 1682-1831 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1952), p. 478

Source: [109] Edwin Wolf and Maxwell Whiteman, The History of the Jews of Philadelphia (Philadelphia, Jewish Publication Society of America, 1957), p. 191; Joseph R. Rosenbloom, A Biographical Dictionary of Early American jews: Colonial Times through 1800 (Lexington: University of Kentucky, Press 1960), p. 7

Source: [110] Myron Sermon, Richmonds lewry 1769-1976: Shabbat in Shockoe (Charlottesville, Virginia: Jewish Community Federation of Richmond by University Press of Virginia, 1979), p. 16

Source: [111] Daniel M. Swetschinski, “Conflict and Opportunity in ‘Europe’s Other Sea’: ‘The Adventure of Caribbean Jewish Settlement,” AJHQ, vol. 72 (1982-83), p. 214

Source: [112] Earl A. Grollman, “Dictionary of American Jewish Biography in the 17th Century,” AJA, vol. 3 (1950), p. 4

Source: [113] Korn, Jews of New Orleans, p. 167

Source: [114] Korn, Jews of New Orleans, pp. 107-9: “Auction,” p. 208, plate 12; 1. Harold Sharfman, Jews on the Frontier (Chicago: Henry Regnery Company, 1977), p. 151

Source: [115] Korn, “Jews and Negro Slavery,” p. 194

Source: [116] Samuel Oppenheim, “An Early Jewish Colony in Western Guiana: Supplemental Data,” p. 43

Source: [117] Samuel Oppenheim, “An Early Jewish Colony in Western Guiana: Supplemental Data,” p. 33

Source: [118] Samuel Oppenheim, “An Early Jewish Colony in Western Guiana: Supplemental Data,” p. 43

Source: [119] Ernst van den Boogaart and Pieter C. Emmer, “The Dutch Participation in the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1596- 1650,” The Uncommon Market, editors, Henry A. Gemery and Jan S. Hogendom (New York: Academic Press, 1975), p. 354

Source: [120] Isaac S., and Susan A. Emmanuel, History of the Jews of the Netherland Antilles (Cincinnati: American Jewish Archives, 1973), p. 75. Belmonte was count palatine and representative of her Catholic Majesty before the High States Ceneral of Holland. Also known as Isaac Nunez, he, jointly with Moseh Curiel, represented the Jews before the Dutch government. In 1658, Belmonte was ambassador-extraordinary of Holland to England; see note no. 55. See also Swetschinski, p. 236

Source: [121] Isaac S., and Susan A. Emmanuel, History of the Jews of the Netherland Antilles (Cincinnati: American Jewish Archives, 1973), p. 76; Johannes Menne Postma, The Dutrh in the Atlantic Slave Trade: 1600-1815 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), pp. 38-4

Source: [122] Harry Simonhoff, Jewish Notables in America: 1776-1865 (New York: Greenberg Publisher, 1956), p. 370, EJ, vol. 4, pp. 529-30; Henry L. Feingold, Zion in America: The lewish Experience from Colonial Times to the Present (New York: Twayne Publishin& Inc., 1974), p. 60; Simon Wolf, The American Jew as Patriot, Soldier and Citizen (Philadelphia: Levytype Company, 1895), p. 114. Whereas most references have confirmed 140 slaves, Feingold has reported the number to be as high as 740

Source: [123] Liebman, The Jews in New Spain, p. 262

Source: [124] Ezekiel and Lichtenstein, p. 90

Source: [125] Max J. Kohler, “Phases of jewish Life in New York Before 1800,” PAJHS, vol. 2 (1894), p. 84

Source: [126] Joseph L. Blau and Salo W. Baron, editors, The Jews of the United States, 1790-1840 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1963, 3 volumes), vol. 3, p. 799. The authors claim that Boyd “was neither a Jew nor a Dutchrnan,” but Samuels describes him as such in a letter to his family in 1819. See also Isaac M. Fein, The Making of An American Jewish Community (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1971), p. 11

Source: [127] Isaac Emmanuel, “Seventeenth Century Brazilian Jewry: A Critical Review,” AJA, vol. 14 (1962), p. 37

Source: [128] Encyclopaedia Judaica (Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House, Ltd., 1971) vol. 4, p. 1411; Schappes, p. 569; Rosenbloom, p. 14

Source: [129] Samuel Oppenheim, “An Early Jewish Colony in Western Guiana: Supplemental Data,” pp. 14, 90

Source: [130] Leo Hershkowitz, Wills of Early New York Jews (1704-1799) (New York: American Jewish Historical Society, 1967), p. 15; Rosenbloorn, p. 14

Source: [131] Samuel Oppenheim, “An Early Jewish Colony in Western Guiana: Supplemental Data,” p. 40

Source: [132] Samuel Oppenheim, “An Early Jewish Colony in Western Guiana: Supplemental Data,” p. 59

Source: [133] Martin A. Cohen, “The Religion of Luis Rodriguez Carvajal,” AJA, vol. 20 (April, 1968), p. 39

Source: [134] Samuel Oppenheim, “An Early Jewish Colony in Western Guiana: Supplemental Data,” p. 84

Source: [135] Korn, “Jews and Negro Slavery,” pp. 181, 195; Ira Rosenwaike, “An Estimate and Analysis of the Jewish Population of the United States in 1790,” PAJHS, vol. 50 (1960), p. 47; Rosenbloom, p. 20

Source: [136] Ira Rosenwaike, “The Jewish Population of the United States as Estimated from the Census of 1820,” Karp, JEA2, p. 18; Korn, “Jews and Negro Slavery,” p. 180; Rosenbloom, p. 21

Source: [137] Ira Rosenwaike, On the Edge of Greatness: A Portrait of American Jewry in the Early National Period (Cincinnati: American Jewish Archives, 1985), p. 69

Source: [138] Encyclopaedia Judaica (Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House, Ltd., 1971), vol. 5, p. 662; Schappes, pp. 101, 593; Korn, “Jews and Negro Slavery,” pp. 185-88; Rosenwaike, “Jewish Population in 1790,” p. 63; Charles Reznikoff and Uriah Z. Engelman, The Jews of Charleston (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1950), p. 77; “Acquisitions,” AJA, vol. 5 (January, 1953), p. 58; Bermon, PP. 163-64; Rosenbloom, p. 24

Source: [139] Encyclopaedia Judaica (Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House, Ltd., 1971), vol. 12, p. 1085; Feingold, Zion, p. 62; Korn, “Jews and Negro Slavery,” p. 189

Source: [140] “Acquisitions. Material Dealing with the Period of the Civil War,” AJA, vol. 12 (1960), p. 117

Source: [141] Rosenwaike, Edge of Greatness, pp. 69-70